On 21 March 2018 leaders of 44 African countries signed an agreement to create the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). The agreement if implemented would remove barriers to trade, such as tariffs and import quotas, allowing the free flow of goods and services between the signatory countries. If ratified by each country the AfCFTA will become one of the world’s largest trading blocs, creating a single market of up to 1.2 billion people and a collective GDP of more than $2 trillion.

Intra-African trade can help industries to become more competitive as it enables them to enjoy more economies of scale and can establish and strengthen product value chains, facilitating the transfer of technology and knowledge through spillover effects. It can also help to attract foreign direct investment which is held back by the small size of markets in individual African countries. Small landlocked African counties especially face difficulties in international trade and are very dependent economically on their neighbouring countries. These difficulties could be eased by the free trade agreement.

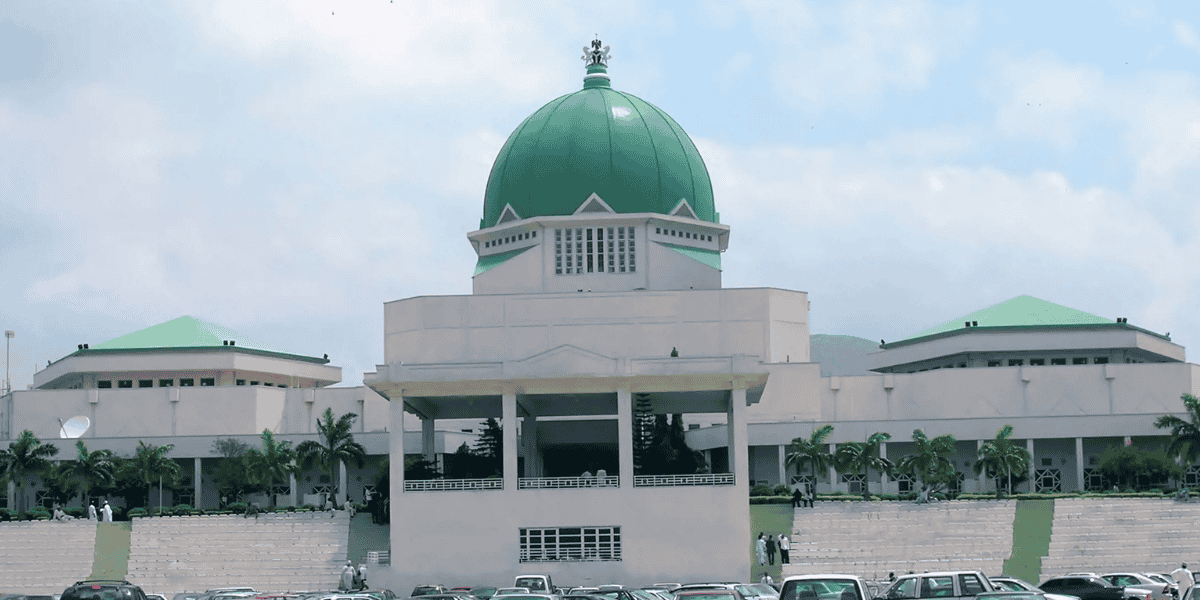

Currently most of Africa’s exports go to advanced industrial economies and most imports also come from those economies. Intra-African trade is quite small although there may be informal trading between neighbouring countries that does not appear in the official statistics. The largest economies Nigeria and South Africa are also the largest intraregional trading economies but they have not yet signed the agreement.

In recent years various regional economic communities have been formed to address the problems of regional integration. Every African country is a member of at least one of the regional groupings and most are members of two or more. These memberships can however create problems by imposing high compliance costs on governments trying to reconcile different regulations. Some regional blocs have however been successful, such as the Southern African Customs Union which has made progress in allowing free movement of factors of production and creating a common tariff on goods from external countries and removing intraregional barriers to trade.

UNCTAD has predicted that reducing intra-African tariffs, one of the conditions of the AfCFTA, could give rise to USD 3.6 billion in gains to the continent through a boost in production and cheaper goods. If the agreement is fully implemented the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa has suggested that intra-African trade can increase by 52% by 2022 when compared to 2010 trade levels. Currently intra-African trade makes up only around 16% of total trade on the continent (according to 2014 figures).

Ten member countries of the AU did not sign the free trade agreement itself, including Nigeria, South Africa, Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, Zambia, Burundi, Eritrea, Benin, Sierra Leone and Guinea Bissau.

South Africa did sign the Kigali agreement to set up the AfCFTA but did not sign the actual free trade agreement because it needs more time to carry out constitutional processes before signing.

The free trade agreement still needs to be ratified by the national parliaments of the signatory countries before the free trade area can come into effect. Even after this the benefits of free trade are likely be held up by the costs of moving goods within African countries and between neighbouring countries. To benefit from free trade African countries need improve the road and rail networks linking them and improve their internal road networks.